Reading time: 7 min.

“Dearest young people, our hope is Jesus. It is He, as Saint John Paul II said, ‘who awakens in you the desire to make something great of your life […], to improve yourselves and society, making it more human and fraternal’ (XV World Youth Day, Prayer Vigil, 19 August 2000). Let us remain united to Him; let us remain in His friendship, always, cultivating it with prayer, adoration, Eucharistic Communion, frequent Confession, generous charity, as the blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati and Carlo Acutis, who will soon be proclaimed Saints, taught us. Aspire to great things, to holiness, wherever you are. Do not settle for less. Then you will see the light of the Gospel grow every day, in you and around you” (Pope Leo XIV – homily for the Youth Jubilee– 3 August 2025).

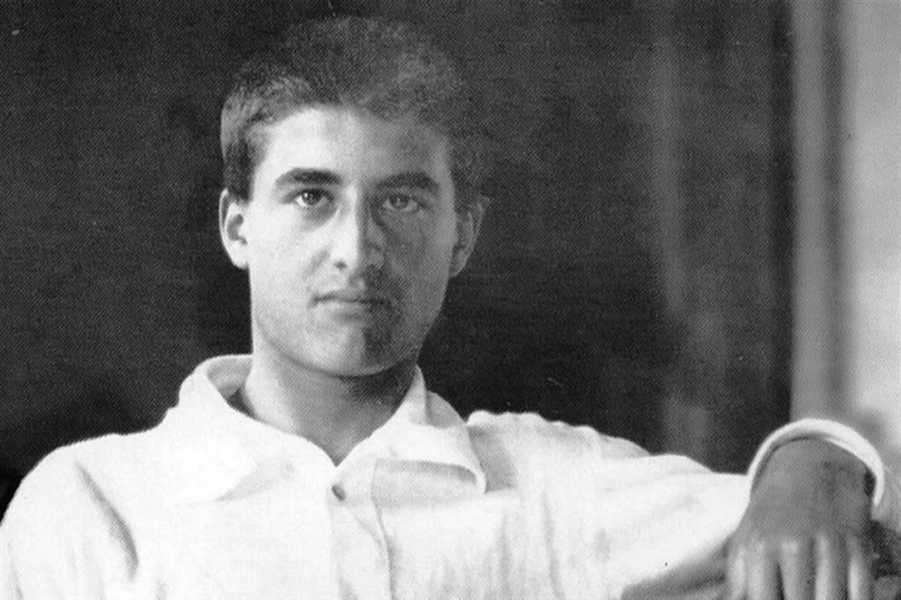

Pier Giorgio and Fr. Cojazzi

Senator Alfredo Frassati, ambassador of the Kingdom of Italy to Berlin, was the owner and director of the Turin newspaper La Stampa. The Salesians owed him a great debt of gratitude. On the occasion of the great scandalous affair known as “The Varazze incidents”, in which an attempt was made to tarnish the honour of the Salesians, Frassati had defended them. While even some Catholic newspapers seemed lost and disoriented in the face of the heavy and painful accusations, La Stampa, having conducted a rapid inquiry, had anticipated the conclusions of the judiciary by proclaiming the innocence of the Salesians. Thus, when a request arrived from the Frassati home for a Salesian to oversee the studies of the senator’s two children, Pier Giorgio and Luciana, Fr. Paul Albera, Rector Major, felt obliged to accept. He sent Fr. Antonio Cojazzi (1880-1953). He was the right man: well-educated, with a youthful temperament and exceptional communication skills. Fr. Cojazzi had graduated in literature in 1905, in philosophy in 1906, and had obtained a diploma enabling him to teach English after serious specialisation in England.

In the Frassati home, Fr. Cojazzi became more than just the ‘tutor’ who followed the children. He became a friend, especially to Pier Giorgio, of whom he would say, “I knew him at ten years old and followed him through almost all of grammar school and high school with lessons that were daily in the early years. I followed him with increasing interest and affection.” Pier Giorgio, who became one of the leading young people in Turin’s Catholic Action, listened to the conferences and lessons that Fr. Cojazzi held for the members of the C. Balbo Circle, followed the Rivista dei Giovani with interest, and sometimes went up to Valsalice in search of light and advice in decisive moments.

A moment of notoriety

Pier Giorgio had it during the National Congress of Italian Catholic Youth in 1921: fifty thousand young people parading through Rome, singing and praying. Pier Giorgio, a polytechnic student, carried the tricolour flag of the Turin C. Balbo circle. The royal troops suddenly surrounded the enormous procession and assaulted it to snatch the flags. They wanted to prevent disorder. A witness recounted, “They beat with rifle butts, grab, break, tear our flags. I see Pier Giorgio struggling with two guards. We rush to his aid, and the flag, with its broken pole, remains in his hands. Forcibly imprisoned in a courtyard, the young Catholics are interrogated by the police. The witness recalls the dialogue conducted with the manners and courtesies used in such contingencies:

– And you, what’s your name?

– Pier Giorgio Frassati, son of Alfredo.

– What does your father do?

– Italian Ambassador in Berlin.

Astonishment, change of tone, apologies, offer of immediate freedom.

– I will leave when the others leave.

Meanwhile, the brutal spectacle continues. A priest is thrown, literally thrown into the courtyard with his cassock torn and a bleeding cheek… Together we knelt on the ground, in the courtyard, when that ragged priest raised his rosary and said, ‘Boys, for us and for those who have beaten us, let us pray!’”

He loved the poor

Pier Giorgio loved the poor. He sought them out in the most distant quarters of the city. He climbed narrow, dark stairs; he entered attics where only misery and sorrow resided. Everything he had in his pockets was for others, just as everything he held in his heart. He even spent nights at the bedside of unknown sick people. One night when he didn’t come home, his increasingly anxious father called the police station, the hospitals. At two o’clock, he heard the key turn in the door and Pier Giorgio entered. Dad exploded:

– Listen, you can be out during the day, at night, no one says anything to you. But when you’re so late, warn us, call!

Pier Giorgio looked at him, and with his usual simplicity replied:

– Dad, where I was, there was no phone.

The Conferences of St. Vincent de Paul saw him as a diligent co-worker; the poor knew him as a comforter and helper. The miserable attics often welcomed him within their squalid walls like a ray of sunshine for their destitute inhabitants. Dominated by profound humility, he did not want what he did to be known by anyone.

Beautiful and holy Giorgetto

In the first days of July 1925, Pier Giorgio was struck down by a violent attack of poliomyelitis. He was 24 years old. On his deathbed, while a terrible illness ravaged his back, he still thought of his poor. On a note, with handwriting now almost indecipherable, he wrote for engineer Grimaldi, his friend. Here are Converso’s injections, the policy is Sappa’s. I forgot it; you renew it.

Returning from Pier Giorgio’s funeral, Fr. Cojazzi immediately wrote an article for the Rivista dei Giovani. “I will repeat the old phrase, but most sincerely: I didn’t think I loved him so much. Beautiful and holy Giorgetto! Why do these words sing insistently in my heart? Because I heard them repeated; I heard them uttered for almost two days by his father, by his mother, by his sister, with a voice that always said and never repeated. And why do certain verses from a Deroulède ballad surface, “He will be spoken of for a long time, in golden palaces and in remote cottages! Because the hovels and attics, where he passed so many times as a comforting angel, will also speak of him.” I knew him at ten years old and followed him through almost all of grammar school and part of high school… I followed him with increasing interest and affection until his present transfiguration… I will write his life. It is about collecting testimonies that present the figure of this young man in the fullness of his light, in spiritual and moral truth, in the luminous and contagious testimony of goodness and generosity.”

The best-seller of Catholic publishing

Encouraged and urged also by the Archbishop of Turin, Monsignor Giuseppe Gamba, Fr. Cojazzi set to work with good cheer. Numerous and qualified testimonies arrived, were ordered and carefully vetted. Pier Giorgio’s mother followed the work, gave suggestions, provided material. In March 1928, Pier Giorgio’s life was published. Luigi Gedda writes, “It was a resounding success. In just nine months, 30,000 copies of the book were sold out. By 1932, 70,000 copies had already been distributed. Within 15 years, the book on Pier Giorgio reached 11 editions, and was perhaps the best-seller of Catholic publishing in that period.” The figure illuminated by Fr. Cojazzi was a banner for Catholic Action during the difficult time of fascism. In 1942, 771 youth associations of Catholic Action, 178 aspiring sections, 21 university associations, 60 groups of secondary school students, 29 conferences of St. Vincent, 23 Gospel groups… had taken the name of Pier Giorgio Frassati. The book was translated into at least 19 languages. Fr. Cojazzi’s book marked a turning point in the history of Italian youth. Pier Giorgio was the ideal pointed out without any reservation; one who was able to demonstrate that being a Christian to the core is not at all utopian or fantastic.

Pier Giorgio Frassati also marked a turning point in Fr. Cojazzi’s history. That note written by Pier Giorgio on his deathbed revealed the world of the poor to him in a concrete, almost brutal way. Fr. Cojazzi himself writes, “On Good Friday of this year (1928) with two university students I visited the poor outside Porta Metronia for four hours. That visit gave me a very salutary lesson and humiliation. I had written and spoken a lot about the Conferences of St. Vincent… and yet I had never once gone to visit the poor. In those squalid shacks, tears often came to my eyes… The conclusion? Here it is clear and raw for me and for you; fewer beautiful words and more good deeds.”

Living contact with the poor is not only an immediate implementation of the Gospel, but a school of life for young people. They are the best school for young people, to educate them and keep them serious about life. How can one who visits the poor and touches their material and moral wounds with their own hands waste their money, their time, their youth? How can they complain about their own labours and sorrows, when they have known, through direct experience, that others suffer more than them?

Not just existing, but living!

Pier Giorgio Frassati is a luminous example of youthful, contemporary holiness, ‘framed’ in our time. He testifies once again that faith in Jesus Christ is the religion of the strong and of the truly young, which alone can illuminate all truths with the light of the ‘mystery’ and which alone can give perfect joy. His existence is the perfect model of normal life within everyone’s reach. He, like all followers of Jesus and the Gospel, began with small things. He reached the most sublime heights by forcing himself to avoid the compromises of a mediocre and meaningless life and by using his natural stubbornness in his firm intentions. Everything in his life was a step for him to climb; even what should have been a stumbling block. Among his companions, he was the intrepid and exuberant animator of every undertaking, attracting so much sympathy and admiration around him. Nature had been generous to him: from a renowned family, rich, with a solid and practical intellect, a strong and robust physique, a complete education, he lacked nothing to make his way in life. But he did not intend to just exist, but to conquer his place in the sun, struggling. He was a man of strong character and a Christian soul.

His life had an inherent coherence that rested on the unity of spirit and existence, of faith and works. The source of this luminous personality lay in his profound inner life. Frassati prayed. His thirst for Grace made him love everything that fills and enriches the spirit. He approached Holy Communion every day, then remained at the foot of the altar for a long time, nothing being able to distract him. He prayed in the mountains and on the road. However, his was not an ostentatious faith, even if the signs of the cross made on public streets when passing churches were large and confident; even if the Rosary was said aloud, in a train carriage or in a hotel room. But it was rather a faith lived so intensely and genuinely that it burst forth from his generous and frank soul with a simplicity of attitude that convinced and moved. His spiritual formation was strengthened in nocturnal adorations, of which he was a fervent proponent and unfailing participant. He performed spiritual exercises more than once, drawing serenity and spiritual vigour from them.

Fr. Cojazzi’s book closes with the phrase: “To have known him or to have heard of him means to love him, and to love him means to follow him.” The wish is that the testimony of Pier Giorgio Frassati may be “salt and light” for everyone, especially for young people today.