Reading time: 7 min.

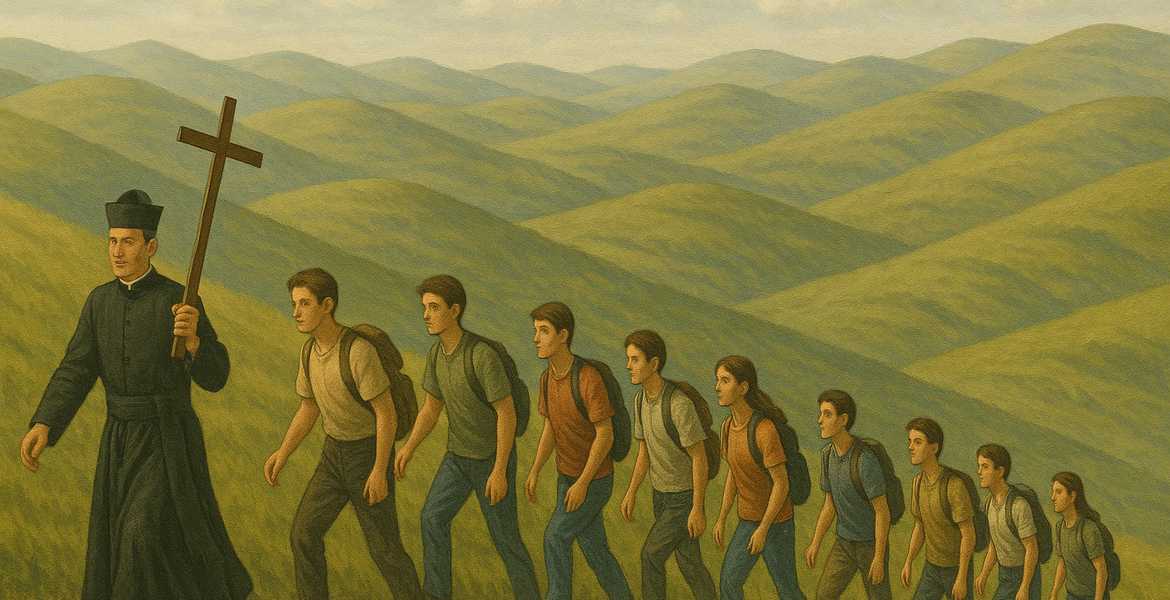

Don Bosco’s dream of the “Tenth Hill”, recounted in October 1864, is one of the most evocative passages in Salesian tradition. In it, the saint finds himself in a vast valley filled with young people: some already at the Oratory, others yet to be met. Guided by a mysterious voice, he must lead them over a steep embankment and then through ten hills, symbolising the Ten Commandments, towards a light that prefigures Paradise. The chariot of Innocence, the penitential ranks, and the celestial music paint an educational fresco: they show the effort of preserving purity, the value of repentance, and the irreplaceable role of educators. With this prophetic vision, Don Bosco anticipates the worldwide expansion of his work and the commitment to accompany every young person on the path to salvation.

It came to him the night of October 21, and he narrated it the following night. [Surprisingly] C …E… a boy from Casale Monferrato, had the same dream, during which he seemed to be with Don Bosco, talking to him. In the morning the boy was so deeply impressed that he went to tell it all to his teacher, who urged him to report to Don Bosco. The youngster met Don Bosco as he was coming down the stairs to look for the boy and tell him the very same dream. [Here is the dream]:

Don Bosco seemed to be in a vast valley swarming with thousands and thousands of boys-so many, in fact, that their number surpassed belief. Among them he could see all past and present pupils; the rest, perhaps, were yet to come. Scattered among them were priests and clerics then at the Oratory.

A lofty bank blocked one end of the valley. As Don Bosco wondered what to do with all those boys, a voice said to him: “Do you see that bank? Well, both you and the boys must reach its summit.”

At Don Bosco’s word, all those youngsters dashed toward the bank. The priests too ran up the slope, pushing boys ahead, lifting up those who fell, and hoisting on their shoulders those who were too tired to climb further. Father Rua, his sleeves rolled up, kept working hardest of all, gripping two boys at a time and literally hurling them up to the top of the bank where they landed on their feet and merrily scampered about. Meanwhile Father Cagliero and Father Francesia ran back and forth encouraging the youngsters to climb.

It didn’t take long for all of them to make it to the top. “Now what shall we do?” Don Bosco asked.

“You must all climb each of the ten bills before you,” the voice replied.

“Impossible! So many young, frail boys will never make it!”

“Those who can’t will be carried,” the voice countered. At this very moment, at the far end of the bank, appeared a gorgeous, triangular-shaped wagon, too beautiful for words. Its three wheels swiveled in all directions. Three shafts rose from its comers and joined to support a richly embroidered banner, carrying in large letters the inscription Innocentia [Innocence]. A wide band of rich material was draped about the wagon, bearing the legend: Adiutorio Dei Altissimi, Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti. [With the help of the Most High, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.]

Glittering with gold and gems, the wagon came to a stop in the boys’ midst. At a given order, five hundred of the smaller ones climbed into it. Among the untold thousands, only these few hundred were still innocent.

As Don Bosco kept wondering which way to go, a wide, level road strewn with thorns opened before him. Suddenly there also appeared six white-clad former pupils who had died at the Oratory. Holding aloft another splendid banner with the inscription Poenitentia [Penance], they placed themselves at the head of the multitude which was to walk the whole way. As the signal to move was given, many priests seized the wagon’s prow and led the way, followed by the six white-clad boys and the rest of the multitude.

The lads in the wagon began singing Laudate pueri Dominum [Praise the Lord, you children – Ps. 112, 1] with indescribable sweetness.

Don Bosco kept going forward, enthralled by their heavenly melody, but, on an impulse, he turned to find out if the boys were following. To his deep regret he noticed that many had stayed behind in the valley, while many others had turned back. Heartbroken, he wanted to retrace his steps to persuade those boys to follow him and to help them along, but he was absolutely forbidden to do so. “Those poor boys will be lost!” he protested.

“So much the worse for them,” he was told. “They too received the call but refused to follow you. They saw the road they had to travel. They had their chance.”

Don Bosco insisted, pleaded, and begged, but in vain.

“You too must obey,” he was told. He had to walk on.

He was still smarting with this pain when he became aware of another sad fact: a large number of those riding in the wagon had gradually fallen off, so that a mere hundred and fifty still stood under the banner of innocence. His heart was aching with unbearable grief. He hoped that it was only a dream and made every effort to awake, but unfortunately it was all too real. He clapped his hands and heard their sound; he groaned and heard his sighs resound through the room; he wanted to banish this horrible vision and could not.

“My dear boys,” he exclaimed at this point of his narration, “I recognized those of you who stayed behind in the valley and those who turned back or fell from the wagon. I saw you all. You can be sure that I will do my utmost to save you. Many of you whom I urged to go to confession did not accept my invitation. For heaven’s sake, save your souls.”

Many of those who had fallen off the wagon joined those who were walking. Meanwhile the singing in the wagon continued, and it was so sweet that it gradually abated Don Bosco’s sorrow. Seven ills had already been climbed. As the boys reached the eighth, they found themselves in a wonderful village where they stopped for a brief rest. The houses were indescribably beautiful and luxurious.

In telling the boys of this village, Don Bosco remarked, “I could repeat what St. Teresa said about heavenly things-to speak of them is to belittle them. They are just too beautiful for words. I shall only say that the doorposts of these houses seemed to be made of gold, crystal, and diamonds all at once. They were a most wonderful, satisfying, pleasing sight. The fields were dotted with trees laden simultaneously with blossoms, buds, and fruit. It was out of this world!” The boys scattered all over, eager to see everything and to taste the fruit.

(It was in this village that the boy from Casale met Don Bosco and talked at length with him. Both of them remembered quite vividly the details of their conversation. The two dreams had been a singular coincidence.)

Here another surprise awaited Don Bosco. His boys suddenly looked like old men: toothless, wrinkled, white-haired, bent over, lame, leaning on canes. He was stunned, but the voice said, “Don’t be surprised. It’s been years and years since you left that valley. The music made your trip seem so short. If you want proof, look at yourself in the mirror and you will see that I am telling the truth.” Don Bosco was handed a mirror. He himself had grown old, with his face deeply lined and his few remaining teeth decayed.

The march resumed. Now and then the boys asked to be allowed to stop and look at the novelties around them, but he kept urging them on. “We are neither hungry nor thirsty,” he said.

“We have no need to stop. Let’s keep going!”

Far away, on the tenth hill, arose a light which grew increasingly larger and brighter, as though pouring from a gigantic doorway. Singing resumed, so enchanting that its like may possibly be heard and enjoyed only in paradise. It is simply indescribable because it did not come from instruments or human throats. Don Bosco was so over

joyed that he awoke, only to find himself in bed.

He then explained his dream thus: “The valley is this world; the bank symbolizes the obstacles we have to surmount in detaching ourselves from it; the wagon is self-evident. The young sters on foot were those who lost their innocence but repented of their sins.” He also added that the ten hills symbolized the Ten Commandments whose observance leads to eternal life. He concluded by saying that he was ready to tell some boys confidentially what they had been doing in the dream: whether they had remained in the valley or fallen off the wagon.

When he came down from the stand, a pupil, Anthony Ferraris, approached him and told him within our hearing that, the night before, he had dreamed that he was with his mother and that when the latter had asked him whether he would be coming home next Easter, he had replied that by then he would be in paradise. He then whispered something else in Don Bosco’s ear. Anthony Ferraris died on March 16, 1865.

We jotted down Don Bosco’s dream that very evening, October 22, 1864, and added this note: “We are sure that in explaining the dream Don Bosco tried to cover up what is most mystifying, at least in some instances. The explanation that the ten hills symbolized the Ten Commandments does not convince us. We rather believe that the eighth hill on which Don Bosco called a halt and saw himself as an old man symbolizes the end of his life in the seventies. The future will tell.”

The future is now past; facts have borne out our belief. The dream revealed Don Bosco’s life-span. For comparative purposes, let us match this dream with that of The Wheel of Eternity, which we came to learn only years later. In that dream each tum of the wheel symbolized a decade, and this also seems to be the case in the trek from hill to hill. Each hill stands for a decade, and the ten hills represent a century, man’s maximum life-span. In his life’s first decade, Don Bosco, as a young boy, begins his mission among his companions at Becchi and starts on his journey; he climbs seven hills-seven decades-and reaches the age of seventy; he climbs the eighth hill and goes no farther. He sees beautiful buildings and meadows, symbols of the Salesian Society which, through God’s infinite goodness, has grown and borne fruit. He has still a long way to go on the eighth hill and therefore sets out again, but he does not reach the ninth because he wakes up. Thus he did not live out his eighth decade; he died at the age of seventy-two years and five months.

What do our readers think of this interpretation? On the following evening, Don Bosco asked us our opinion of the dream. We replied that it did not concern only the boys, but showed also the worldwide spread of the Salesian Society.

“What do you mean?” a confrere countered. “We already have schools at Mirabella and Lanzo, and we’ll have a few more in Piedmont. What else do you want?”

“No,” we insisted. “This dream portends far greater things.”

Don Bosco smiled and nodded approval.

(1864, BM VII, 467-471)