Reading time: 4 min.

The discovery of an unpublished letter from Don Bosco always offers an opportunity to shed light on lesser-known aspects of his pastoral, educational, and publishing work. The document presented here, recently found and now kept at the Central Salesian Archive in Rome, is part of the vast collection of the Turin saint’s correspondence and confirms his pedagogical vision: to favour simple and accessible language, capable of reaching peasants, workers, and the poorly educated rather than intellectuals. This letter, written in the context of the “Letture cattoliche” (Catholic Readings), reveals not only his respect for the diocesan rules of the time but also his clear awareness of the role of the “good press” in an era of great political, cultural, and religious transformation.

The context of the document

It is the one preceding the advent of the Kingdom of Italy (1861), ten years after the granting of freedom of the press (1848) in the Savoy kingdom, a freedom that had been welcomed even by those who previously were not free to propagate their religious ideas (various Protestant denominations, Jews…). Don Bosco, who had already been engaged for some time in the publication of books and pamphlets for the youth and the people, especially devotional and formative texts, then took the field directly in defence of the Catholic faith that he saw endangered.

In 1853, at the urging of the bishops of Piedmont and in collaboration with the bishop of Ivrea, Bishop Luigi Moreno, Don Bosco had started the “Letture cattoliche” (Catholic Readings), a monthly publication of a few dozen pages, in a reduced format, with a didactic slant, sometimes polemical in tone. His own writings and those of other authors appeared in it. From 1862 it was printed in-house at Valdocco and distributed throughout Italy through an enviable network of priests and lay people willing to become promoters of what would later be called “the good press”. Among the many priests who for various reasons would set foot in Valdocco, perhaps to recommend some of the village children to Don Bosco, one day Fr Bernardino Francione, a rather cultured priest from Grignasco parish (Novara), must have come too. Given the Salesian printing house and the series of “Catholic Readings”, he must have had the idea of publishing a booklet on the sacrament of Confirmation as part of that series.

Having said that, some time later he sent the manuscript to Don Bosco, who, in deference to the diocesan regulations in force, submitted it to the ecclesiastical reviewer established by Archbishop Luigi Fransoni (in exile since 1850 in Lyons).

The judgement of the unknown censor – who apparently knew the popular nature of Don Bosco’s “Catholic Readings” well – was as follows: “The work is good and could be printed without difficulty, if it is intended for educated people; but for these readings it would be necessary to remove everything that looks like an objection: make the words and sentences as popular as possible, add some similes or examples that can allow the lower classes and poorly educated Christians feel its moral implication.”

A significant note

Don Bosco would have fully shared this judgement: he was interested in children, young people, the semi-illiterate Italian population, not intellectuals or learned people. The series he was editor for had a very simple target, the popular class made up of peasants, workers, artisans, mothers of families. And hence he added his own significant note from this perspective to the moderately positive judgement of the reviewer: “My feeling, however, would be that you imagine you are speaking to your parishioners and instructing them about the sacrament of which we are speaking here and about the way to make First Communion well.” So he asked Fr Francione – to whom he erroneously attributed the title of parish priest (actually Fr Giuseppe Boroli at the time) – for a written text that had the flavour of the spoken word, was more colloquial in tone, more like popular preaching, with various suggestions for living a moral life according to the most common criteria of the popular mentality of the time.

The fortunes of the Catholic Readings

It does not appear that the above-mentioned priest’s booklet was ever printed in the Catholic Readings, nor elsewhere: the name of the author and title of the book does not appear in the encyclopaedia of printed writings of the 19th century. But the fact remains that the Catholic Readings were an immense success. Starting with a print run of about 3,000 copies, they reached about 12,000 in the 1870s: an enormous result for the time. Kept at very low prices, they were the flagship of the Valdocco printing house, which obviously put hundreds of other volumes on the market, from large dictionaries and texts for schools to hagiographic and apologetic operettas, books and pamphlets on history, religious instruction, devotional character, and circumstance.

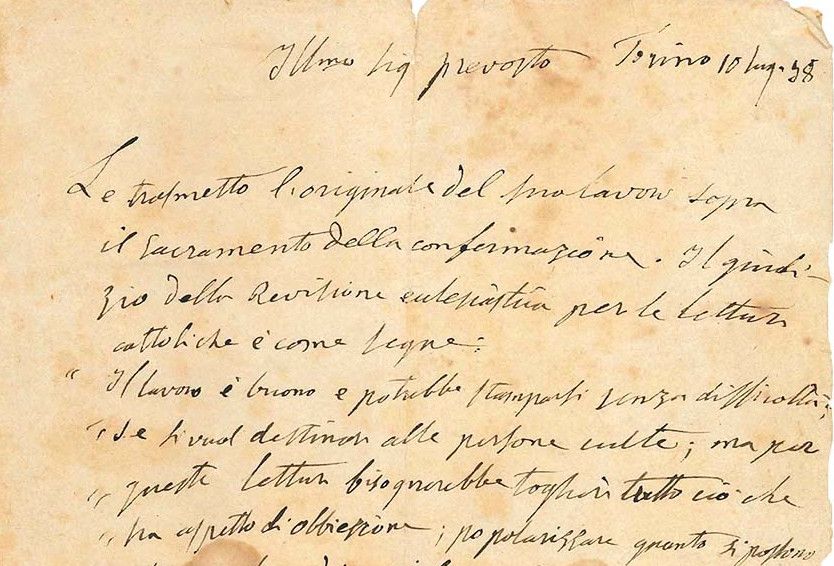

Here then the letter.

Turin, 10 Jul 58

My Lord Provost,

I send you the original version of your work on the Sacrament of Confirmation. The judgement of the Ecclesiastical Review for Catholic Readings is as follows:

“The work is good and could be printed without difficulty, if it is intended for the devout; but for these readings it would be necessary to remove everything that has the appearance of objection; to popularise the words and phrases as much as possible; to add some similes or examples that can leave moral sentiments in the lower classes and in poorly educated Christians.”

My feeling, however, would be for you to imagine you are speaking to your parishioners and instructing them about the sacrament of which we are speaking here and about the way of making First Communion well, as we said when I had the pleasure of seeing you here at the Oratory.

At any rate, I will always wholeheartedly remain your devoted servant, Fr G. Bosco.