Reading time: 4 min.

The mystery of Christmas begins with a scandal of love: the Great becoming small. It is not a poetic image, but the most disruptive reality in human history.

God, the Infinite, chooses to become finite; the Almighty chooses the fragility of a newborn who cannot yet speak, walk, or defend himself. It is pure gratuitousness manifesting itself, a gift that asks for nothing in return, that sets no conditions for access.

1. Recognising gratuitousness: God comes unconditionally

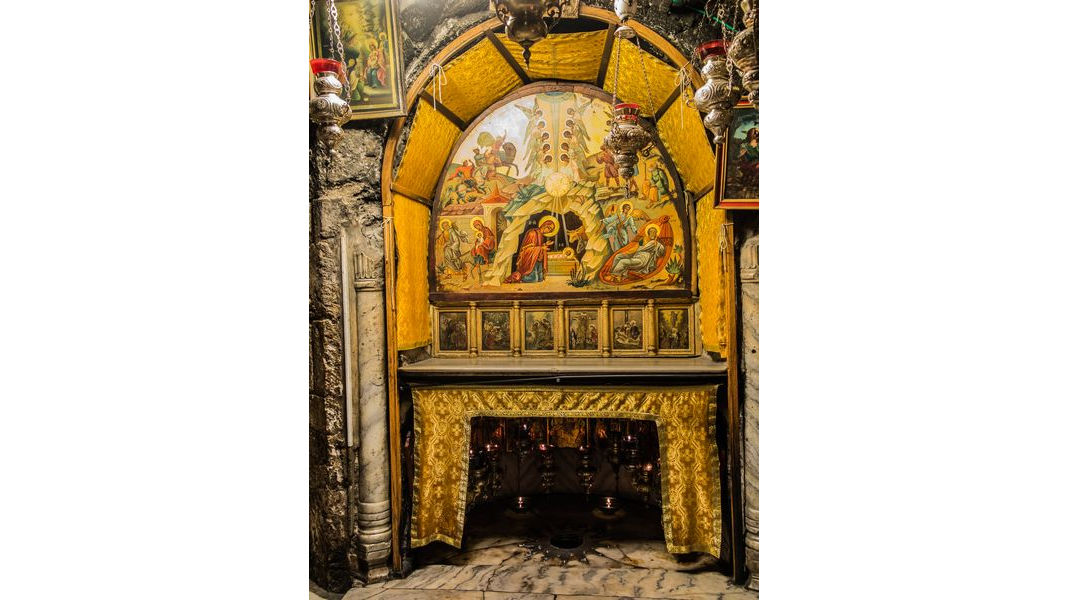

The grotto of Bethlehem is the humblest human crossroads imaginable. Not a palace, not a majestic temple, not even a decent house. A grotto, an animal shelter, where the cold penetrates and the smell is that of earth and straw. Here there are no entry barriers, no invitation is needed, no special attire is required. The door is open to all: to shepherds with their worn cloaks, to the poor, to the excluded, to those who have nothing to offer but their wounded humanity.

Saint Paul reminds us with words that span the centuries, taking the form of a servant (Phil 2:7). The Creator of the universe strips Himself of His glory, renounces His divine prerogatives, to put on the clothes of a servant. He does not come as a conqueror, not as a severe judge demanding accounts. He comes as one who serves, as one who takes the last place, as one who washes feet even before teaching to walk.

This gratuitousness deeply challenges us. In a world where everything has a price, where every relationship seems based on exchange, where love itself often becomes conditional, Christmas reminds us that a completely gratuitous gift exists. Recognising this gratuitousness means accepting to be loved without merit, to be sought when we are still far off, to be desired when we feel unworthy.

2. Interpreting closeness: God enters our history

The second movement of Christmas is that of radical closeness. God does not observe human history from afar, like a detached spectator. He enters into history, with its protagonists as they are: imperfect, contradictory, fragile. Joseph with his doubts, Mary with her fears, the shepherds with their social marginalisation, the Magi with their restless search.

Our personal history, with all its dark folds and shadowy areas, is part of His story. We are not strangers; we are not unwanted guests. We are sons and daughters, part of a family that God never disowns. Christmas tells us that God does not despise His creation, does not look at His creatures with disgust or disappointment. On the contrary, He embraces them precisely in their concreteness, in their authentic humanity.

Each of us has a unique personality, an unrepeatable story. There are those who are exuberant and those who are reserved, those who are strong and those who are fragile, those with open wounds and those with hidden scars. God meets us exactly where we are, not where we would like to be or where we think we should be. He meets the alcoholic in his bar, the prisoner in his cell, the exhausted mother in her kitchen, the student in his solitude, the elderly in their silence.

But this closeness is not static; it is not resignation. God meets us where we are to lead us where we deserve to be. We do not deserve it for our efforts or our virtues, but we deserve it as beloved children. We deserve the fullness of life, deep joy, recovered dignity, healed relationships. God’s closeness is dynamic. It is an outstretched hand that invites us to rise; it is a voice that whispers “come further”; it is a presence that walks beside us towards brighter horizons.

3. Choosing acceptance: Truth knocks at the door of freedom

And here is the third movement, perhaps the most delicate: acceptance. In the grotto, the game of our life is played out. It is not rhetorical exaggeration, but the deepest truth of our existence. That grotto is the image of every inner grotto of ours, of those hidden spaces of the heart where we decide who we want to be.

Truth – which is not an abstract idea but a Person, that Child in the manger – knocks at the door of our freedom. It is a discreet, gentle knock, never violent. God could break down the door, could impose Himself with the power of His omnipotence. But He chooses to beg. The Divine becomes a beggar of humanity. What an astonishing paradox! He who created everything asks us, His creatures, to make room for Him.

Truth calls, waiting for Freedom to respond. There is no coercion, no manipulation. There is only an invitation, renewed every day, every moment; “Will you welcome me?” It is human freedom, fragile and powerful together, that must decide. We can close the door; we can pretend not to hear; we can postpone until tomorrow. Or we can open.

Choosing acceptance means recognising our indigence. Just as that grotto was an empty space ready to be filled, so too must we empty ourselves of our presumptions, our self-sufficiencies, our idols. Acceptance requires inner space. We cannot welcome God if we are already full of ourselves.

But when we choose to open that door, when we say our yes, the miracle happens. The poor grotto becomes a cathedral of light. Our ordinary life becomes a place of Presence. Our fragilities become spaces where grace can operate. Acceptance transforms; we are no longer the same after having welcomed that Life that comes to visit us.

Christmas, therefore, is this threefold movement that involves us entirely. It is recognising the scandalous gratuitousness of a God who makes himself small; interpreting the closeness of Him who enters our concrete history. It is choosing acceptance, opening the door of the heart to the Truth that knocks. In the grotto of Bethlehem, as in the grotto of our heart, everything is decided. Every Christmas is an opportunity to answer again that ancient and ever-new question, “Is there room for Him?”